We Might Not Like It, But What If There Are People We Can’t Reach?

It’s hard for someone who considers themselves liberal and even believes that people are born good, to admit that there are some people who are so far gone that they're unreachable. We might have even wondered for a long time how any country could have so many who idolized an Adolf Hitler enough to elect him for a second term as Chancellor.

Today, as we look at the current President of the United States and the seemingly blind adoration he receives from his followers, we’re forced into a more existential understanding of what we would call the immovable right-wing on the extreme of a spectrum of human beings. Yet, it’s still difficult to face any other human being and decide that the best strategy for our own and our country’s well-being is to give up trying to change them.

Are we willing to say that our current state of psychological and psychiatric science has not yet found the tools to help people who’ve been so traumatically damaged through their life experiences so that there’s no known cure? And what if, instead of turning for help, these damaged people have taken to using leadership, followership, or their powerful position as a means not to heal personally but to act out their hurts on others in a way that destroys so many around them?

The idea of giving up on any human being, especially one who is family or a friend is sure to trigger all our own abandonment issues, liberal guilt, and fears that others might give up on us. There’s little rational about our responses to that thought and much that keeps us trapped into trying to change the lost while we function for them instead as their enablers.

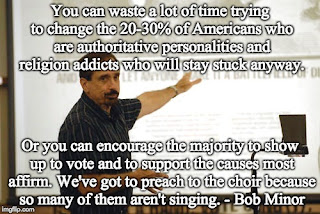

The immovable have always been there. Scholars have labelled them authoritative personalities or ones who are like users for whom their addiction is to a charismatic leader or even a form of religion. And the expert on authoritative personalities, Robert Altemeyer who’s studied them since the rise of Hitler in Germany has estimated that maybe 30% of Americans fall into this category.

If these people have not been able to rise to leadership, they’re prone to become caught up in personality cults and to subject themselves to a leader such as the right president or the right religious personality. Nothing that the object of such a cult does or says, even to the point of jeopardizing their own lives (Jonestown is a popular example) will cause these people to doubt the one for whom they’ve given up their ethical thinking and on whom they’ve bet their lives.

If these people have not been able to rise to leadership, they’re prone to become caught up in personality cults and to subject themselves to a leader such as the right president or the right religious personality. Nothing that the object of such a cult does or says, even to the point of jeopardizing their own lives (Jonestown is a popular example) will cause these people to doubt the one for whom they’ve given up their ethical thinking and on whom they’ve bet their lives.

The authoritative followers’ language becomes rhetoric that rises not out of their own thoughtfulness but repeats what they’ve been told almost word for word. Their slogans are meant to shut down conversation and dialogue and to provoke a response and frustration, or as they say today: “to own the libs.”

There will always be a way for these followers to justify their wayward or hypocritical cultish leader. Denial, ignoring of any facts presented, anger at those who disagree, violence against their defined enemies, and belligerence are so predictable that to be surprised by these responses is a sign of being caught up in one’s own desperate and often baseless hope that things were otherwise.

And for these cultish followers to change as a result of any evidence or persuasion would be for them to admit that they’ve been duped. Each con they’ve fallen for from their idols makes it harder for them to face the fact that they’ve been taken. It’s all deeply emotionally threatening and related to insecure self-concepts.

They will always be able to find groups of the likeminded who will provide the company that reinforces their stuckness. And they will assume that most people who challenge them are the duped.

Recognizing our inherent emotional optimism, then, in spite of the fact that there are people who will not change no matter what we do, what can we do?

1. Whether we like it or not, we’ll have to make imperfect judgments about who these people are. That won’t be easy because we’ll be prone to think otherwise. We’ll have a difficult time not thinking that just a little more dialogue or persuasion might save this person, convert them, or soften them up. It will be hard to apply the 3 “Cs” of AL Anon: “You didn’t cause it, you can’t control it, and you can’t cure it.”

2. We’ll have to decide whether continuing attempts to change or win this person are good for them. Are our ongoing attempts instead enabling them and hardening their positions by giving them the chance to argue abstractly about the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, tradition, the Bible, God, (you name it) instead of forcing them to deal with the personal issues that are covered up by these abstractions they claim are the basis for their ideas and being.

3. We’ll have to decide whether continuing attempts to change this person or win these people are good for us. How much energy does this take away from everything else we have in our lives? Are there other people for whom our efforts are more likely to make a difference and thus involve a better, more effective use of our time and energy – the moveable middle? Is the frustration level that results worth it to me and to those who need my attention?

4. When do I decide that this person or group is so toxic to myself and/or others that my best strategy would be working to protect others from them? How much of their continual hurting of others by their words and actions should be accepted while I spend time working to change them? When should I move to do work to blunt or eliminate their influence?

5. What guilt feelings do I have, if I decide to walk away? How am I blaming myself and my lack of doing enough for their intransigence? Why do I feel that I am the person to fix this other? Why can’t I just show clearly and forcefully that I disagree with them? Why do I think that I haven’t expended enough effort with them yet? Can I still live with myself if I do move on? If not, why not?

To choose to move on from these people doesn’t require anger, ill feelings for, or retaliation against them. It’s also not evidence of same failure on our part.

It means making sure that we are clear to them that we disagree, that they know they are standing in front of some real human being who they offend because they’re hurting others, and that they know that they will not move us from, or make us compromise, our core human values.

It means making sure that we are clear to them that we disagree, that they know they are standing in front of some real human being who they offend because they’re hurting others, and that they know that they will not move us from, or make us compromise, our core human values.

It’s like doing an intervention rather than enabling. And then feeling what emotions doing so are triggered in us.

Doing the right thing doesn’t always feel right. Compassion is not the same as doing things that make us feel that we’re one of the “nice” ones.

Standing up for justice is difficult work and includes the idea that patterns of injustice that have been learned can be unlearned. But it also means we can’t change everyone.

So, is there a point where we should write someone off personally to get on with the work of changing the world and its structures in order to stop the human suffering involved without being deflected by trying to get the agreement of those who won’t change?

Comments

Post a Comment